In 1953, Liu took part in the creation of the relief on the foundation of the Monument of People’s Heroes at the Tiananmen Square, acting as an assistant to master sculptors Liu Kaiqu and Wang Bingzhao. He specifically contributed to the drafting of the relief entitled The Jintian Uprising.

As one of the first generation of young sculptors trained in new China, he benefited a lot from his teachers of the aforesaid department who imparted to their students solid Western art education they had learned in France, and particularly from Wang Linyi who taught him nude portrait exercise and creative lessons. After returning to the academy in 1954, he once worked as a teaching assistant to master sculptor Zeng Zhuyun. Instead of joining the academy’s mainstream sculptural artists, he embarked upon an independent and a long journey to explore his own art after coming across with traditional and folk Chinese arts while living at the bottom of society.

Today when we come close to this old artist and look at the superb collection of his sculptures, we cannot help being moved by not only his legendary life, but by his art works created by heart. Liu, like many of his contemporaries, represents the cream of the 20th century’s Chinese intellectuals who hold fast to their own moral and spiritual principles. However, Liu’s personal history also reflects in one way or other ups and downs the Chinese sculptural development has undergone over the past century. And many of the related cultural phenomena deserve further studies by art historians today.

Liu Shiming’s art assumes different keynotes in different historical periods.

I. Spirited and Romantic Youth

In 1946, Liu was admitted to the National Art College of Beiping and became one of the first group of students personally chosen by Xu Beihong, president of the college. The college was established in 1918 with majors of fine arts, music, and drama, the earliest of its kind in Chinese history. Thanks to his diligence, Liu excelled in his studies very soon.

His graduation work Measuring the Land (1949) depicts the joy of the peasants in suburban Beijing during the land reform. These peasants, who have straitened up their back after toiling and suffering in the old days, are filled with happiness and yearning for a new life ahead. Always concerned about the creation of this works, Wang Linyi believed that Liu had very a good artistic feeling and told him to keep up this fresh feeling. Later this works was not only awarded in a contest of creative works held by the academy, but also collected by the National Museum of former Republic of Czechslovakia (now the Czech National Museum).

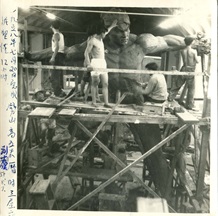

In 1951, Liu’s sculpture-Heroes in the Volunteer Army, was erected in the central flower terrace at a crossroads of the Wangfujing Commercial area. In 1956, he was invited to work in Wuhan, capital of Central China’s Hubei Province, where he created within 9 months a giant sculpture in collaboration with Sculpture Wu Shiwei, for the Hanyang end of the Yangtze River Bridge.

In 1958, he created a big sculpture entitled Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow, portraying the inspiring and hard-working spirit of that era.

In 1959, the work was enlarged and renamed Removing the Mountains and diverging Rivers at the suggestion of the famous painter Hua Junwu. The work was later exhibited in Moscow and won sweeping critic accolades. The work was believed to be one to represent the lofty spirit of the time when the Great Leap Forward movement was in full swing.

This giant work of sculpture was erected at the entrance to the Zhangshan Park and its picture was published nationwide and became almost a household sculpture to all Chinese families.

The famous Chinese writer Zhou Yang called it “an eternal piece of art.” The senior artist Qian Shaowu called it “one of the very few works that will go down in China’s sculpture history.”

The work that was later enlarged in cement was bought by the municipal government of Baoding at the price of RMB 4000 yuan, and erected in the Dongfeng Park of this city as the symbol of Baoding and image of the people living around the Taihang Mountains. It is indeed rare that the sculpture still stands in the park safe and sound. In 1959, Liu took charge of creating a group sculpture entitled Unity between Officers and Men for the Chinese Military Museum and the centerpiece for the Beijing Workers Stadium.

It may be said that Liu Shiming, as a young sculptor then appreciated by the famous painter Xu Beihong and highly regarded by sculptors of the older generation, was high-spirited, bringing his talent into full play and enjoyed a rosy prospect. His works during this period, and especially the monumental giant ones, echo the vigorous spirit prevailing in the early days when new China was founded.

II. Liu’s Middle–aged Bitterness and Perseverance

Since the 1960s, dramatic changes have taken place in Liu’s life. He left Beijing and came to live in Henan and Hebei provinces. After leaving his family, he began to lead a life full of frustrations and setbacks. But he did not lose his confidence in life. On the contrary, while living with the people who were at the bottom of society, he understood their philosophical view and their kind nature.

As a result, major changes took place in his art. His exploration deep into the spiritual world of the Chinese people shows the humanitarian sentiments of a Chinese sculptor. In his works, the most precious thing is a tranquil and philosophical view of man’s life and warmth of human nature.

According to the recollection of his friend Jin Zhilin, after quitting the academy and coming to Henan, Liu Shiming worked for 10 years in the Zhengzhou Art Academy and Kaifeng normal institute (today’s Henan University), and then was seconded to work in the Henan Provincial Museum, Hebei Baoding Cultural Centre for the Masses, and finally the National Museum of Chinese History (now the National Museum of China).

During this period, Liu was engaged in restoration and reproduction of cultural reics. He coped and reproduced a large number of colored pots and Han Dynasty pottery figurines. They include Yangzhao colored pottery of the Majiayao Culture, the jade animals and figures from the FuhaoTombs of the Yinxu Ruins, the bronze tigers, boars and buffalos excavated at the Shizhaishan Ruins of Southwest China’s Yunnan Province, ancient storytelling figurines, Han Dynasty figurines, Persian figurines unearthed from the sites along the Silk Road and a small-scale totem featuring a galloping horse treading a flying swallow underfoot, the Qin Dynasty pottery works, pottery stoves of the Xia Dynasty, Tang Dynasty saucers unearthed in Xinjiang, and ancient wooden passports worn at the waist.

The large amount of painstaking restoration and reproduction work he has done offers him a chance to absorb, understand and make an in-depth study of ethnic history and culture, as well as folk art traditions so that his art has been raised to a new height.

(Folk Sculptor Liu Shiming by Jin Zhilin, carried in the Collected Works of Liu Shiming, compiled and published in 1988 by the Department of Sculpture, Central Academy of Fine Arts )

Talking about his work during this period, Liu said, “I am deeply impressed by the traditional Chinese art and its technique of expression. The Qin Dynasty figurines are so realistic that they are even more vivid and expressive than our works today. For instance, not only joints of their hands, their eyes and beards, but also their finger nails and even their shoestrings are meticulously carved. Every detail of their armor and even their different facial expressions showing different characters have made clear their ethnic feature.

As for the Han Dynasty figurines, focus is on the spirit exaggeration. They are done in a less complicated and realistic way. I am most touched by the sculpture Story -Telling Figurine of the Han Dynasty. Its posture and facial expression are so exaggerating, vivid and accurate while the anatomy of its bones and muscles, the expression of its eyebrows and wrinkles and even its toenails are so expressive in exaggeration without any stress on its arms and hands. I once reproduced a Yuan Dynasty brick sculpture that features stage characters with some of them whistling, and a Song Dynasty brick relief that portrays a pretty woman working in the kitchen.”

Since the mid 1970s, as he was seconded to work in the Chinese History Museum Liu have studied the traditional Chinese pottery figurines and ancient bronze ware, and conscientiously drew on the Chinese traditional art and especially the vividness, sprit and flavor of the story-telling figurine in his works.

The exotic imagination made use of by the ancient artists in integrating animals with utensils has influenced his works such as Pottery Vessel with Three Women (1981), and Tiger Carrying on Its Back A Woman.

In 1980 Liu came back to teach in the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which has greatly inspired his creative passion and therefore his creations entered a new height. He created a large number of works reflecting the lifestyle and customs of Henan and Hebei and urban life in Beijing such as Farmhouse series, Cave Dwelling series, Ansai Waist Drummer, Man Playing Suona, Boatmen on the Yellow River, Zhuizi Ballad Singing from Henan Province, and Bangzi Clapper Operas from Shanxi Province.

Thanks to the establishment of the studios of hard materials and electric kilns in the academy at that time, Liu had the opportunity of focusing on the creation of pottery works. One type of his works is about the daily life of both rural and urban people, heavily influenced by the Han Dynasty pottery towers. The other type is in fact the products of modern pottery art integrating human figures and animals with vessels--pottery works of no practical use.

Full of innocence, free imagination and passion, these works bespeak the artist’s persistence in life and art. Many of his works with meticulous composition and expression come from his keen observation of life and long-term accumulation in his life.

It is the period after reflecting on the academic education he received in the West, Liu began to study and integrate himself with the Chinese traditional art.

Hua Tianyou, Liu Shiming’s teacher, is one of the pioneering sculptors in modern China devoted to the comparative study of Western and Chinese sculptural art. In his view, “The creation of Western sculpture usually starts with its contour, and then comes to its details step by step and finally integrates its details with the entirety, therefore it is accurate in proportion and anatomy. Realistic, vivid and lifelike are the strong points of Western sculpture. The Chinese painting and sculpture are concise in style, which are first focused on lines and surfaces. Unlike merely copying their objects, they are imposing and distinctive in style by finding its rules, and look impressive and unforgettable. Due to lack of anatomic study in Chinese sculptural art, the aforesaid strong points in Western sculpture might be absorbed in and applied to our creations.” (A Brief Biography of Sculptor Hua Tianyou by Liu Yuehe, p.10, first edition in June 1993, published by People’s Publishing House of Fine Arts.)

Liu’s sculptures are by no means mere reproductions of folk fine arts. Like spring rain, he has blended the education he received with a frank and free expression This free expression of his mind is just like the calm and innocent approach to nature adopted by the ancestors of the Han Dynasty. Therefore, on the basis of Chinese traditional sculpture and Western realistic sculpture, he has developed a sculptural style with a strong Chinese flavor that is modest and easy of approach, magnanimous and confident, and made his contribution to the development of Chinese sculpture today.

The middle-aged Liu also created works often giving expression to his romantic sentiments hidden deep in his heart. For instance, his 1982 work Someone Who Wants to Fly portray a legendary figure in Chinese history with two big wings ready to fly into the blue sky. As resurrection of the romantic imagination in his youthful years, this sculpture is in fact a symbol of the Chinese people living at the bottom of society yearning for a leap forward, and also reflects pursuit of freedom by the emancipated mind and Chinese nation’s spirit of working hard for the prosperity of their country in that era.

The keynote of his 1986 work Man Playing Suona and 1989 work Ansai Waist Drummer from Ansai is high-spirited. His 1989 work Youthful Days features a group of young girls dancing gracefully in the wind with their arms joining their long hair.

III. Prosaic and Tender in Old Age.

Love is an important theme for Liu’s works. Love expressed in his art is the broad-minded love. For instance, his works not only express the love between lovers like Lovers (1983) depicting two young lovers chatting on a long chair in a park, Lovers in the Imperial City (1983) featuring a fashionable couple embracing each other on the street, and In Love (1988) depicting a boy and a girl sitting together, head over heels in love.

His works also depict love between mother and son, such as Bathtime (1989), and Mother Returns (1990), love between family members like Hold Me, Grandma (1992), as well as love between the army and people, ordinary people and animals such as Seal Mother and Child (1993), Monkey Mom and Child (1994), and Pigeons (1995).

Liu’s 1983 work Performer Backstage depicts the love between mother and son, which gives a vivid portrayal of some actresses of a country local opera troupe feeding and pissing their babies during the intermission. Unique as it is in shape, his 1989 work Baby in a Lotus Leaf is also based on a real life story.

His 1991 work Eternal Love: the Continuation of Life is unique in shape, featuring a little boy standing upside down on the head of his father, their shared joy beyond words.

What he depicts is the most essential and eternal sentiments of man’s daily life, (such as childlike innocence and selfless mother’s love), which are the finest qualities touching the hearts of people at any era and in any society.

Liu sometimes even uses such phrases as tender and quiet, honest and kind to describe the figures of his creative works. It is these qualities and sentiments that have helped us tide over the most difficult time in our life, and fill us with confidence in our life and future.

In the late 1980s, boatmen’s life became an important topic in his creation. He has portrayed a large number of boatmen and peasants such as A Family on the River, and Wooden Raft on the Yangtze River (2004). He depicted all sorts of boats and different farming tools used on the boats.

I am often wondering whether the large number of boats and boat dwellers created by Liu, apart from depicting what he has seen and felt about in real life, express his awareness of human life and long river, as well as progress and struggle.

If not, he would not have always remained so interested in this topic –Starting from his early work Woman Back to Her Boat created in the 1950s to his old-aged works such as Boatmen on the Yellow River (1996), and Wooden Raft on the Yangtze River (2004).

To Sum up, Liu Shiming’s sculptural art has the following characteristics.

First, he is very keen of the changes in our era.

Liu has always kept his eyes open to the life of ordinary Chinese people in the changing era, which is shown in hid early works Measuring the Land (1949), and Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow (1958), in his middle-aged works Soldiers from the People's Liberation Army Repairing Houses after the Earthquake (1980), and the latest works Residential Building (2005). For instance, Residential Building depicts some Beijing residents gathering and chatting in front of the new residential building they have just moved in. It shows both the residents’ joy over their improved living conditions, and their fond memories of the interesting life spent in the old courtyard houses.

Liu is not only concerned about the worsening of rural environment as shown in his work Desertification (2000), but also pleased with the rapid urban development he has witnessed in Beijing after returning to the city, which is shown in his works the busy Cement Carrying Trucks on the Construction Site, the Beijing residents who have moved from Siheyuan Courtyard (2004) to Residential Building (2005), and Disc Venders depicting rural women selling porn discs on Beijing’s streets, carrying their babies as camouflage.

Liu’s keenness of new things in life comes from his love of life. The natural life and its free expression depicted in his works shape up vividness and simplicity –the most precious thing in his sculptural art. What we find in his works look like proto-life, but it is in fact the most vivid thing he has extracted from the life that has impressed him. Thus, rendering poetic sentiments for daily life, he has made his plain works lasting in history.

Second, Liu keeps improving his art creations.

To express his understanding of a given topic, Liu would create many of his works with the same topic such as A Fisherwoman Returning Home (1956), Female Educated Youth Street Cleaner (1981), Man Playing Suona, Tiger Carrying A Woman on Its Back, Mother (1993), Performer Backstage (1990s), and Self Portrait, Farmhouse and Boatmen on the Yellow River.

His creations are similar to those of Chinese writers and painters. They have yielded their desired results through repeated creations and readjustments, whigh can’t be achieved through one hasty creation.

Third, Liu loves Chinese traditional operas.

He is so crazy about them that he has frequented Jixiang Theatre while living in the Wangfujing area. He loves best the traditional folk operas and especially local operas like bangzi.

Liu has collected records of many famous actors of Heibei bangzi, Shanxi bangzi and Henan bangzi. He would not miss any opera programs shown on TV. After watching them, he would often portray with clay, according to his recollection, the characters and scenes of these operas.

From Liu’s 1993 work General Zhao Yun and 1994 work General Zhao in the Battle of Changbanpo, we can see the daring and gallant characters of traditional operas. Different from the stereotypical and decorative style of folk art, the figures he has created are characterized with his distinctive handwork, and therefore they assume their own unique personalities and postures.

It is clear that the freehand brushwork technique of expression unrestrained shifts like floating clouds and flowing water adopted by the traditional Chinese operas have exerted a subtle influence on Liu’s sculptural art. It is a moving legendary story that he and Ma Jinfeng, the famous performing artist of the Henan local opera, have developed a life long friendship in art.

Fourth, Liu is concerned about and keenly observant of daily life, and focuses his attention on some special scenes and customs.

His 1984 work Repairing Shoes depicts a humorous scene: sitting on a stool, a young couple are watching the cobbler repairing their shoes; and finding no place to rest her bare foot, the girl puts hers on the boy’s foot. Such details can be often found in his works, and make people break into understanding smile.

Man with a Man with Boat and Cormorants (1986) depicts a scene on the bank of the Yellow River: local peasants, carrying wooden boats and fish hawks, are on their way to catch fish.

Tiehua Going to Make Noodles (1998) depicts a scene of daily life: a university professor pushing his bike to buy noodles. Popcorn (1998) portrays an old vendor of the between-meal nibble, most welcomed by the little kids at that time in China. He produces popcorn with the corn or rice kids have taken to him from their home in a heating stove within 10 minutes. With a big bang, the air is filled with the aromas of the popcorn that will make your mouth water.

At that time, coal was rationed and supplied to people with ration books. To save consumption of coal, urban residents usually mixed some clay into coal. Some peasants would pull their carts carrying such mixture of clay and coal and sell it to urban people from house to house, a cartful worth RMB 2-3 yuan.

His 1998 work A Girl Pulling A Cart of Mixture of Coal and Clay reflects part of the urban life in the 1960s. As such a life has faded away from big cities today, it is hard for the younger generation to imagine what those days are like. His works have left us a living memory of that era.

Birds’ life is the most favorite subject for Liu’s works in old age. It reflects his kind nature and tender heart.

In his 1990 work Looking At Each Other Across the Cage, Liu depicts a big sparrow standing outside a cage and a small one inside the cage, looking at each other. Such a scene of confinement and resignation is much food for thought.

His work Looking at Each Other Through a Cage (1990), depicts two sparrows standing hesitantly by a bird-trap and chirping, as if consulting whether they should risk catching food inside the bird-trap.

In his work Sparrows (2005), Liu depicts a mother sparrow carefully feeding her baby sparrow, a heart-warming scene in the sunshine. Every day, these sparrows would fly onto the windowpane of his flat, and enjoy the food spread there by Liu. Shine or rain, he would sit by the window, awaiting their arrival, and the birds have become part of the life of his twilight years.

Another topic of Liu’s sculptural works is about rural courtyard houses, such as Underground Cave Dwelling in Luoyang (1997), Cooking (1997) and Feeding Lamb (1999). From his pottery representations of cave dwellings or courtyards on China’s loess plateau, following his magic fingers, we can get a bird’s view of the most proto-rural life for thousands of years: livestock yelling in their shed, piglets eating in the trough, chicken jumping and dogs barking, a rural scene full of vitality.

As far as ancient Chinese sculptural history is concerned, we may find cultural relationship between Liu’s pottery works and pottery towers in the Han Dynasty. More precisely speaking, Liu’s works come from real life rather than art history. He has seen and been impressed by the simple country lifestyle described by Jin Dynasty poet Tao Yuanming, and presented before us with his magic hand China’s simplicity and harmony existing in China’s rural houses.

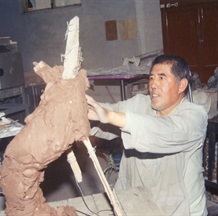

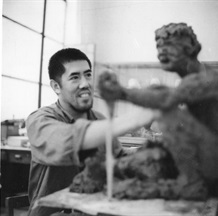

Liu Shiming has the unusual ability of handling different sculptural subjects and moulding them with ease. Touched by no matter what kind of subjects and objects, he would pick up a big lump of clay, letting his feelings flow freely in his hand, and life reborn in his clay creation.

His work Game of Throwing Sandbags depicts the postures and expressions of the three girls at play, which is like a vivid sketch, and we seem to hear the cheerful giggling of the girls. In my view, the animals depicted in his works Cormorants on the Yellow River (1998) and Lonesome Lion (1999) are full of childlike playfulness and vivid humor, and can become the prototype for children’s cartoons.

Many of the sculptural works Liu created in his later years are based on his recollections of the past, which is his impression of life as if done in sketch. Although advanced in years, he still cherishes high aspirations. While recalling his hard life, a lot of unforgettable people and events rush to his mind and then appear in his works. While a CCTV shooting crew were making a documentary about him in his home for the program Son of the East, I had the honor to observe the process of his artistic creation. His attentive face bathed in the sunshine coming in from the window, he picked up a handful of clay, and like a folk artist moulding a dough figurine, he quickly produced a vivid sculpture with his hand.

Of the traditional Chinese sculptures, he likes most the Han Dynasty figurines. While working in the Chinese History Museum, he spent a lot of time observing and emulating the figurines and horses of the Han Dynasty and was engaged in copying and reproducing them. He is deeply touched by the charming postures and expressions demonstrated in the artworks created by our ancestors. In his own creations he has absorbed the sincere spirit of simple expression and straightforwardness from Chinese traditional and folk art. His sculptural art has inherited and developed the great tradition of Chinese national and folk art, occupying a unique and an irreplaceable position in development of Chinese sculptural art in the 20th century.

I would like to quote a Chinese couplet as a clear-cut summary of Liu’s sculptural art.

Here is the couplet: one must embrace life, tradition, and passion; one must have faith, spirit, and soul. Its horizontal scroll reads: Acting to your heart’s content. I believe what the couplet proposes is the most valuable core of real art and the fountain of unique artistic creativeness.

What has sustained Liu’s life is his passion for sculptural art from the bottom of his heart. For him, sculpture means livelihood, life, and faith. Assessing an artist and his works, the most important thing is to find whether he has faith and his works spirit. Such faith in life and art is more precious in our era in which people are increasingly going after worldly gains. Qing Dynasty scholar Liang Qichao once pointed out, “Faith is sacred. For a man, it is his vital energy, and for a society its vital energy too.”

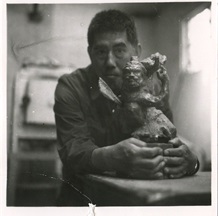

Liu’s 1988 work Self Portrait is both one of the few such works (which was reproduced in 2000 and 2002), and a rare piece revealing his self-reflection. Judging from its content, it is the work showing Liu’s recollection of his early years spending in a Beijing courtyard house.

A kettle singing on a stove in Liu’s small and simple room, he leans over a chair lonely, like a Buddhist statue, lost in deep thought, with only a small bird by his side. In his thoughtful eyes, we see an unbending faith rather than frustration and resignation. It is this faith that has sustained his hard life, and wrought through hardships and setbacks his soul-penetrating sculptural art.

Most of Liu’s works are products based on his deep understanding of real life. As he has spent his lifetime at the bottom of society, he portrays what he has seen and thought over. Though his seems the creative approach of the classical realism, his works contain positive understanding of man’s life, and much of human philosophy is expressed in a sigh and looking at one another in silence.

Liu usually expresses his aspiration in life with unique romantic composition. His style is much different from the realistic style feature only socialist ideas and policy preaching.

Liu’s works, like old wise men in rural China telling stories to children on a summer night on the threshing ground, moisten the hearts of the younger generation like spring rain with implication and principles of man’s life, carry forward China’s folk traditional culture and keep alive the Chinese nation’s spirit and kind nature.

Far from perfect as the world is, people can’t bear to part with their life. Liu Shiming once composed a poem as the summary of his life and sculptural art:

Amidst the flames of the kiln,

I cherish a tender feeling.

A hard trek through winding dirt path,

Leads me finally into the sunshine.

Torn between the rights and wrongs,

I drift in the world of man.

In Liu’s view, no matter how many things one can get in his lifetime, he has to bid farewell to the world leaving all his things behind.

Liu Shiming blends his life philosophy with his works. To him, some small changes would take place every day in the life of most ordinary Chinese, without the possibility of big changes taking place in their life.

Therefore, as far as the changing style of Liu’s sculptural works is concerned there are no big ups and downs. With a slow tempo, he approaches the original life he has led, which is filled with complex but tender sentiments. While appreciating his works, we would be touched by the plain daily life of the common people and their love and affection and betray an understanding smile, but in fact we have realized the helplessness and bitterness embodied in the hard life of the ordinary people living at the bottom of society. When looking at his 1980 work Handcart, 1983 work Performer Backstage, and 2002 work Self Portrait, what has filled my heart is not only respect for the ordinary people who face their hard life with and indomitable will, but a bit of melancholy.

So Liu Shiming considers his art a natural expression of what he has seen in and felt about life. He neither regards his works as important masterpieces, nor trade them for fame and position in life. Though he loves his works, he is always pleased to give away his works free of charge whenever others like them. Apart from his sculptural art, he has nothing and no other wish in life. As sculptural art is his best love, the reason he has presented his works to others means he would like to share with his bosom friends his heart. Up to now, his works that have been collected by his friends who love his art are countless.

It is also because Liu does not want to gain worldly fame and fortune with his works that he is not interested in fashion and style prevailing in this era. Always doing what he likes to, he has sincerely and earnestly pursued his own course of art. In other words, it is his life spent at the bottom of society and far away from the cultural hub of metropolitans, disengagement from worldly fame and position as well as the hardships and frustrations he has undergone that has produced his art, and rendered for his art a unique character a world different from the mainstream art. Like the aroma coming from the wine stored underground for years, the strong flavor from the mixture of the life of ordinary Chinese living at the bottom of society and Chinese traditional art is seeping into our hearts.

Due to historical reasons and restrictions on artistic creation, Liu Shiming did not get many orders for the creation of sculptures and few of his works are gigantic and eye-catching monumental. Therefore we need to take time and patience so as to appreciate his works. At first glance, they look fairly plain, but we will feel the profound implications hidden in them if watching and observing them again and again. As his art is the crystallization of his life experience and efforts, we should spend more time appreciating and understanding it.

Since the exhibition of Liu Shiming’ sculptures held in the National Art Museum of China, I have seen a lively activity of sculptural art going on there in 2006. Ju Ming and Xiao Changzheng, two famous sculptors from Taiwan, Wen Lou from Hong Kong and Wu Weisha from the Nanjing University, have held their own large-scale solo-show respectively. As it is no easy task for sculptures to hold solo shows the holding of the aforesaid exhibitions have far-reaching significance.

Different as they are in their features, these solo shows share something in common, which gives us much food for thought. From Chinese Taichi boxing Ju Ming has found the right expression in his sculptures. Xiao Changzheng develops his sculpture based on the natural space. Wen Lou uses bamboo to demonstrate the moral character of Chinese literati. Wu Weishan focuses on portraying great figures and masters in Chinese history as well as well-known academics and artists of China today. What Liu Shiming depicts is nothing but the ordinary Chinese living at the bottom of society, small fish-fries and their plain life.

These exhibitions have, to a different degree, had a bearing on both the independent development of Chinese sculpture and how its own cultural roots can be found in the course of China’s art modernization in the 20th century, and its own national art identity can be established in the world art arena. Proceeding from the older generation of artists who have studied abroad, introduced Western art in our country and made their own creative contributions, and art exploration pursued by the aforesaid sculptural masters, we can at long last discuss the historical topic in the 21st century in earnest—China’s modern sculpture, or the modern nature of China’s sculpture.

Liu Shiming’s sculpture makes us reflect on whether there should be our own value norm and criteria for aesthetic judgments of China’s contemporary sculpture. What are the details of this norm? What is its relations with China’s aesthetic scope and conception such as character, style, mind, spirit and charm?

The senior artist Qian Shaowu once discussed in his article published in the journal Art Research the artistic characteristics of Chinese traditional sculptures and especially spirit, charm and strength of character, which would have something to do with drawing on and contemporarily transforming Chinese traditional culture and art. Many elder sculptural artists such as Zeng Zhuyun, Hua Tianyou, Wang Linyi and Liu Kaiqu have attached great importance to the Chinese traditional culture and made much valuable exploration in this respect.

How can we carry forward their aesthetic ideals and develop contemporary Chinese sculptural art today? Over the past 50 years and more, Chinese sculptors have done a great deal of work in this respect. As a student taught by the sculptors of China’s first generation who studied in France, Liu has made an important contribution to this topic by devoting his life to sculptural art and his sculptural show has helped us understand better this historic mission.

In-depth study of his sculptural art may help us broaden our vision and realize there are diversified approaches to developing Chinese sculptural art. Proceeding from China’s native culture is an invaluable way of exploration worth trying.

Yin Shuangxi, PhD, is a renowned art critic and sponsor based in Beijing.