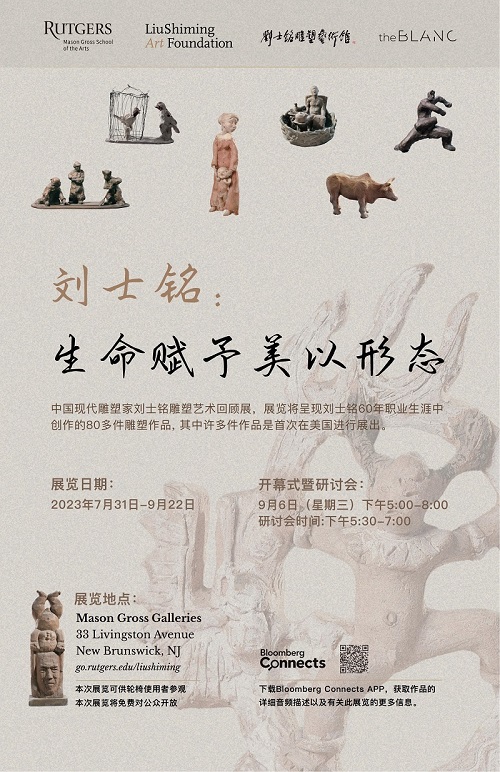

Recently, “IN THE HEART OF THE BRONZE: A Liu Shiming Experience”, which is the 9th overseas solo exhibition of the outstanding Chinese sculptor Liu Shiming, was held at the Western University (University of Western Ontario) in Canada. Through his sculpture works which transcend time, culture, and identity, especially his famous "China Practice" works—a series of small sculptures that combine personal experience, aesthetic creativity, and cultural experience together, Liu Shiming has again touched the hearts of viewers who are in completely different spatial, time, geographical, and cultural states.

As one of the first group of sculptors cultivated by the Central Academy of Fine Arts (abbr. CAFA) after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Liu Shiming's career was closely related to the birth of modern Chinese sculpture. However, due to various complex factors such as the special historical situation of China in the mid-20th century and his own personal experience and spontaneous choices in work creation, Liu Shiming has long been an overlooked figure in the history of Chinese sculpture. As the academic circles deepen their research on the history of sculpture so in recent years have seen a growing recognition of Liu Shiming's exploratory contributions to modern Chinese sculpture.

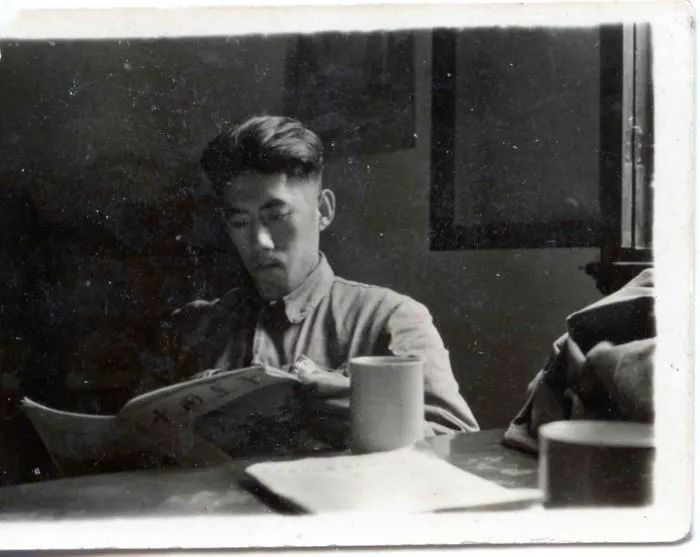

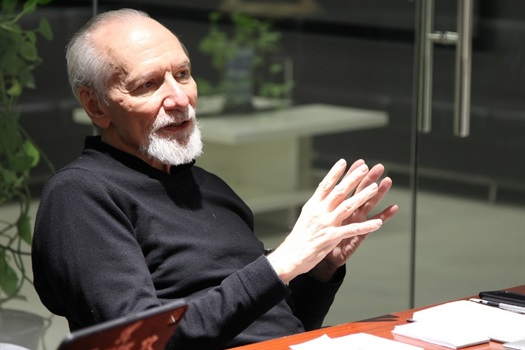

Liu Shiming

01. Academic Lineage: From Rodin, Bouchard, and Wang Linyi to Liu Shiming

In any attempt to examine the influence on Liu Shiming’s early training in sculpture, we will find that French realism is only a part of such influence. Modern Chinese sculpture emerged in the early 20th century, when the first group of Chinese students of sculpture went to study in the West then proactively introduced the Western sculpture system into China. From Li Tiefu in the early days to Liu Kaiqu, Wang Linyi, Zeng Zhushao, Hua Tianyou, Wu Zuoren, Wang Ziyun, among others, most of these students who studied sculpture in France and Japan returned to China and joined various art colleges in the country to set up sculpture departments and train Chinese sculptors. In 1946, Liu Shiming was admitted to the National Beiping Art School and studied under China’s first group of modern sculptors Wang Linyi, Hua Tianyou, and Zeng Zhushao. In terms of technique, style, and philosophy, he did not only benefit from the solid realist skills of the French academic school brought back by his three teachers from École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, but also inherited the Rodin sculpture system that still dominated both inside and outside the French academic school in the early 20th century.

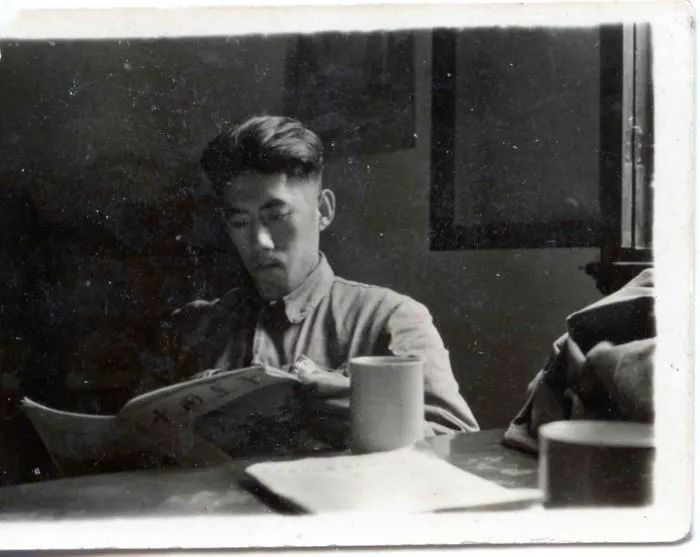

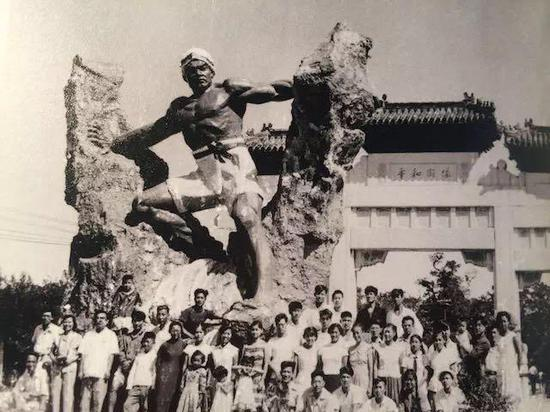

The Group Photo When Liu Shiming graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1950

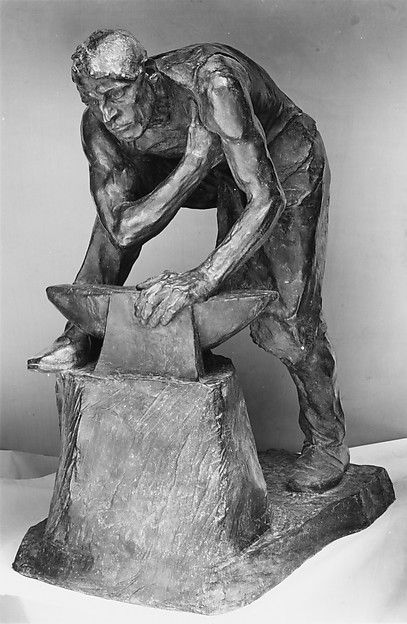

Wang Linyi, Hua Tianyou, and Zeng Zhushao all studied under Henri Bouchard. Liu Shiming’s early training in sculpture was mainly influenced by French realism, but it was also mixed with more complex artistic elements such as the Gothic artistic style that profoundly influenced Bouchard's works and French social realist art, just like Bouchar’s “socialism-oriented” sculpture works [1], which favored portraying the common class and the lower class of society, such as reflecting farmers, fishermen, and workers, once influenced Wang Linyi's socialist inclinations in his thematic works such as National Unity and Returning to the Embrace of the Motherland. [2]

The Blacksmith by Henri Bouchard (1907)

Emphasizing the shaping of the body of sculpture as an important feature of the French realistic sculpture tradition, and this influence is also reflected in academic teaching at CAFA. It can be seen from Liu Shiming’s recollections of the teaching of his three teachers in his memoir. For example, he recalled, “Mr. Wang Linyi repeatedly reminded me, ‘You need to pay attention to the sense of weight.’ A few days later, when he saw my sculpture, he told me, ‘You need to pay attention to the overall shape.’” Mr. Hua Tianyou once taught him the "small-point ball collection method" of the French academic school. Liu Shiming summarized it like this, "Mr. Hua's technique is a blend of Chinese and Western elements, with Chinese elements at the mainstream and Western elements as the reference. In Mr. Hua's works, one can see how he organizes the sculpture structure into several major facets to make the form look strong and powerful, as well as the beauty of a properly constructed composition.” It was also Mr. Hua who absorbed traditional Chinese sculpture techniques and created the "basket weaving method" which stressed the use of lines. From the direction of Chinese culture, this inspired Liu Shiming's perception of national art, promoting him, with his mastery of the language of Western modern sculpture, to further understand his own cultural positioning and direction of exploration. In 1955, Liu Shiming became Mr. Zeng Zhushao's assistant. He still remembers Mr. Zeng teaching the technique of three points forming one side in his human portrait class. By repeatedly searching for the interweaving relationship between the blocks, “plane is created out of no plane. So, Mr. Zeng said what he created was an invisible plane. It was not a round and soft one, but a unified and real image of an old man with bones inside and facial features outside”, to create a strong, vivid, and realistic character statue.

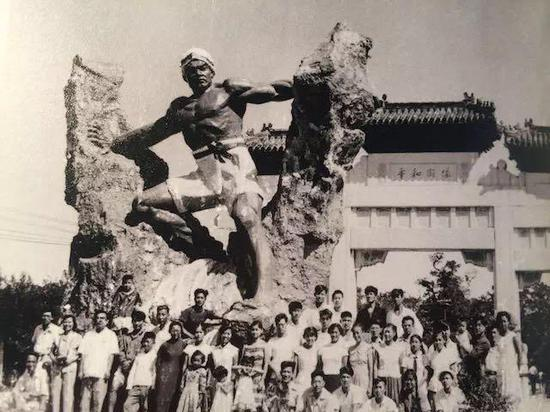

Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow 1 by Liu Shiming (1958), Glazed Earthenware, 15.8×18.8×9.5cm

Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow 3 by Liu Shiming (1970), Bronze, 23.2×9×21.8cm

Influenced by French realist techniques and artistic ideas, Liu Shiming's student career fell into the stage of the "Mao Zedong era after the founding of the People’s Republic of China" as defined by Mr. Zou Yuejin. Under the guidance of several teachers and driven by his natural artistic instinct, Liu Shiming developed his sculpture skill and style as being strong in the creation of “facets” [3], as manifested in his specific works. For example, Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow that he created in 1958 was full of a revolutionary and romantic spirit. Combining a solid and powerful styling, the surging dynamic posture of the character, and an extraordinary imagination together, the work constructs and conveys a certain kind of inner passion.

As a monumental sculpture, the work showcases a familiar rough passion and exaggerative techniques that emphasize imagination, which instantly reminds people of Antoine Bourdelle, another master who deeply influenced Liu Shiming's teacher Wang Linyi. As Rodin's most famous student, Bourdelle was once an assistant to Rodin. Today, in Bourdelle’s famous sculpture works such as The Great Warrior of Montauba and Hercules the Archer, one can vaguely see from the similar style of "sculptures depicting the intensity of survival" [4] the pursuit of volume and quantity that Liu Shiming may have indirectly learned from the generation of his teachers who returned to China from studying in France, as well as their use of exaggerative and deformative techniques that are not completely detached from the real world, which are used to explore the origins of the expression of the core humanistic spirit in monumental sculptures.

The Great Warrior of Montauba by Antoine Bourdelle (1898-1900)

Hercules the Archer by Anthony Budell (1909)

02. Civic Perspective, Daily Life, and Tactile Perception

Apart from the influence on techniques, how has Liu Shiming inherited the ideals of Zeng Zhushao, Hua Tianyou, Wang Linyi, Liu Kaiqu, and others in developing modern Chinese sculpture? What explorations has Liu Shiming made in the development of contemporary Chinese sculpture? How can we understand the modern factors explored in Liu Shiming's artistic works? What exploratory paths can they still offer as implications for the present day?

The question firstly concerns how to define the starting point of modern Chinese sculpture. There are currently two main theories in academic circles about when modern sculpture started in China. One view is that it began in the 1920s when the Western sculpture system was introduced to China by the first group of Chinese students studying abroad, and modern Chinese sculpture started basically in synchronization with modern Chinese art. Another view is that modern Chinese sculpture commenced in the 1990s when Chinese sculptors showed more self-awareness towards the modernist context. [5] The definitions of "modern" are vague and varied. If we take the view that "Some art that is rarely connected to previous art forms or even forms a state of breakage from them is called ‘modern’" [6], namely the birth of new art form, then it may not be inappropriate for looking at sculptures that actually appeared since the 1920s as the beginning of modern Chinese sculpture. If we further place Liu Shiming in the modern coordinate system of the birth of this new art form, one of the modern factors contained in his explorations may be roughly summarized as a choice of work creation from a civic perspective. Liu Shiming has a very clear idea of this, saying: "I belong to the thought and social class of the common people, and I have always stood alongside working people to see things." [7]

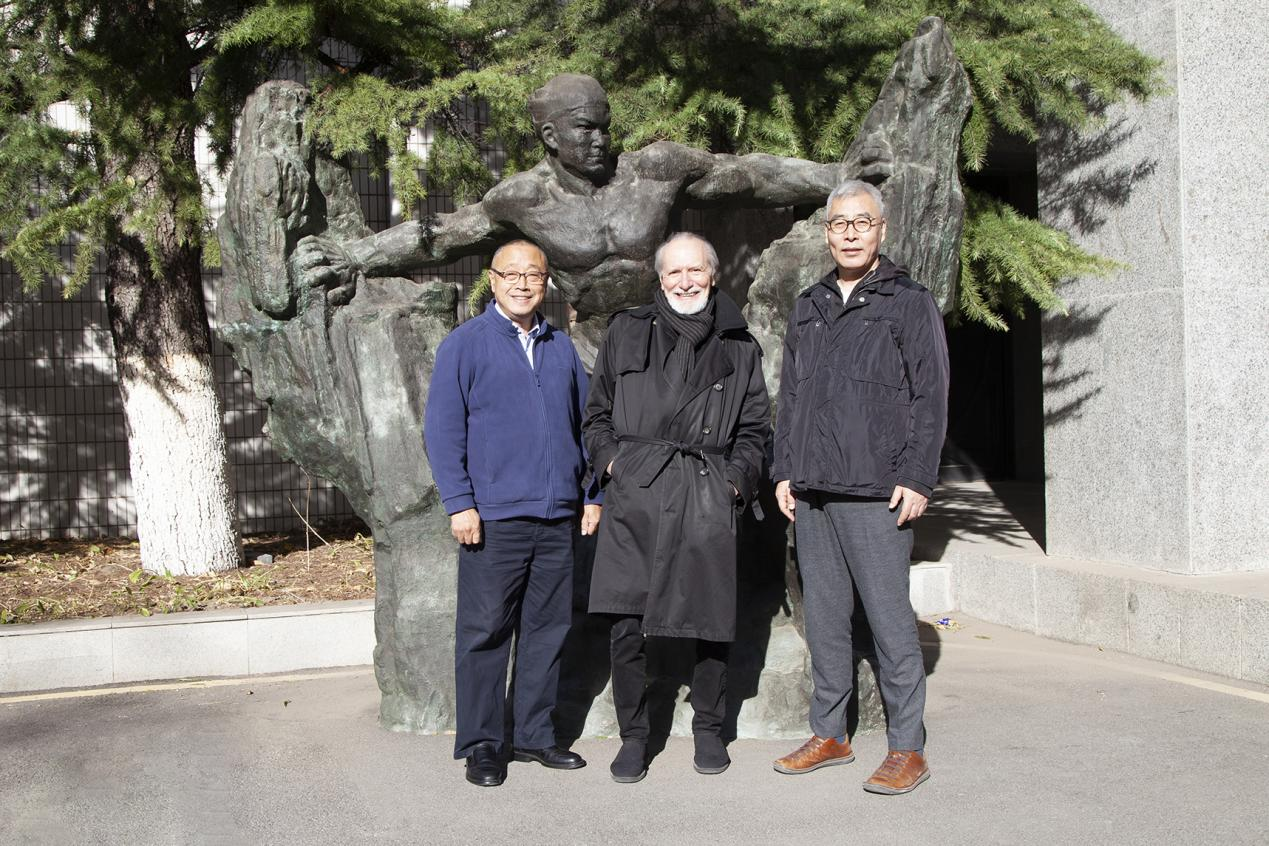

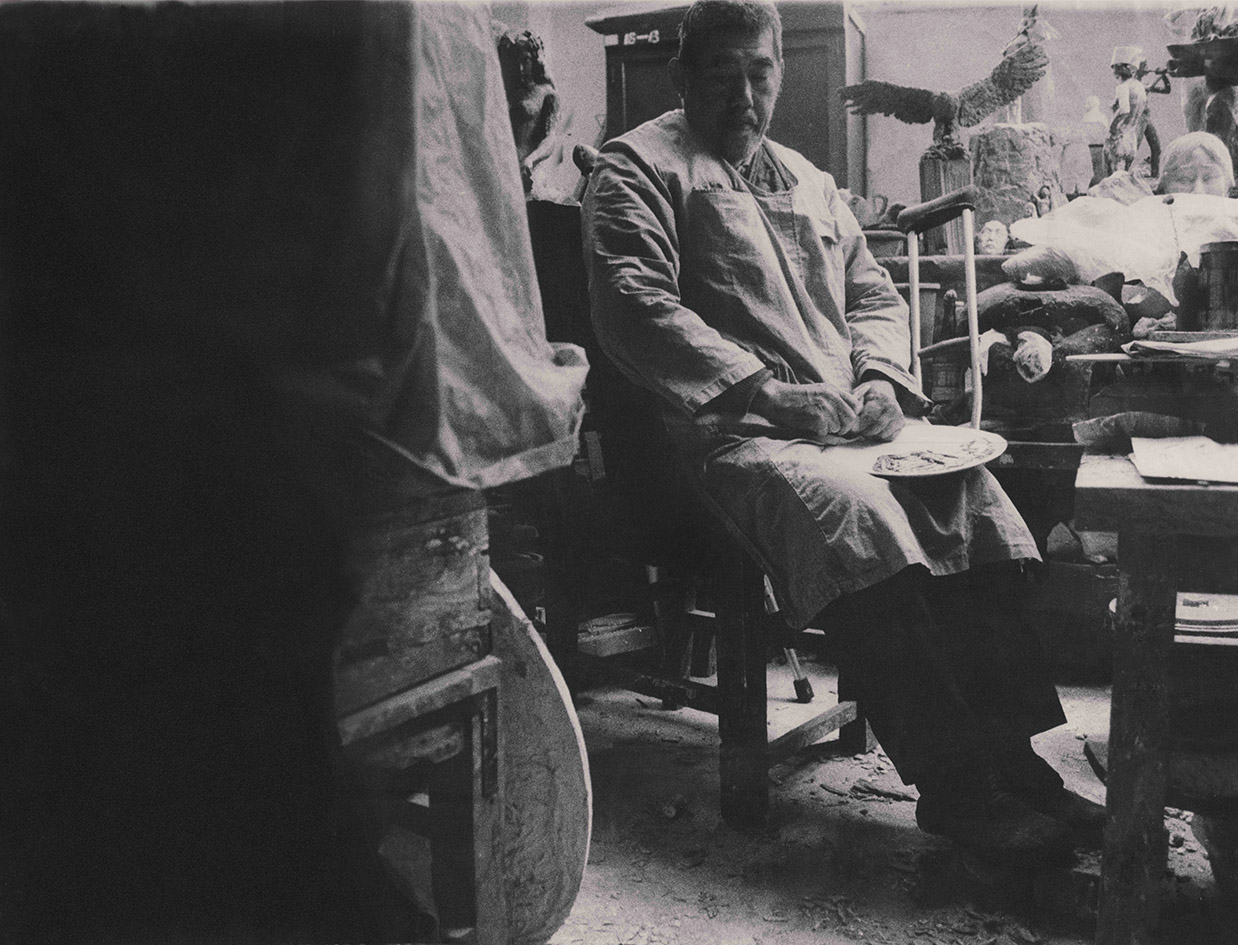

Liu Shiming at the Chinese Sculpture Factory

Specifically in his works, this manifests as a civic perspective that the artist himself still holds even when dealing with grand historical events and mythological themes. This is evident in the images of three old candid farmers portrayed in his work Measuring the Land which Liu Shiming created in 1949, which portrayed the land reform movement in China, and in Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow, which portrayed a great civilian hero as a tribute to the July 1 birthday of the Communist Party of China. The latter not only combines the techniques of traditional Chinese colored sculpture with Western sculpture, making it a pioneering work of modern Chinese colored sculpture, but also portrays a heroic spirit and an image of the extraordinary power of splitting the mountain to let the water flow. It is also widely believed to represent the image of working people on the land of Yan and Zhao (i.e. Hebei Province in northern China) rather than the heroes in mythology. It was precisely for this reason that when many statues across the country were damaged during the Cultural Revolution, the sculpture Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow was well preserved. The similar exaggerated techniques and civic perspective may remind people of another sculpture full of satire and animation by Daumier, known as the pioneer of modern sculpture. From the works of the two artists which have vastly different themes, people can see a certain artistic attitude that deviated from traditional sculpture right from the start of material selection.

Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow was installed in front of the Defending Peace Square in Zhongshan Park, Beijing

Moreover, the artist attaches great importance to daily themes and selects materials accordingly. On the one hand, based on his life experience and out of consideration for convenient work creation, Liu Shiming chose more convenient clay materials to create smaller works as China entered a new stage of reform and opening-up. He did not rely on sketches but more on the re-instillation of emotions and memories. Therefore, his works often rely on a quick capture of emotions and memories. Combining traditional hand sculpture in folk art, it facilitated the artist to capture inspiration in fragments from his life experiences, thus giving rise to a certain "sketching" factor and highlighting a form of modernity that occurs between theme and material. Richard Vine, an internationally renowned contemporary art critic, saw a parallel relationship between material and theme in Liu Shiming's clay sculpture works: "The theme comes from daily life, and the material comes from everyday clay." [8] Vine saw a Duchamp-style impulse to overthrow a certain established tradition bound to materials. This factor, which does not pursue a sense of completion in the classicism but instead goes for immediacy or even has a certain characteristic of recording, also this once appeared in many Western modernist artists such as Degas, Matisse, and others. They, like Liu Shiming, mastered artistic skills but chose to actively break from tradition. Perhaps this is not a coincidence, but more out of a desire for "innovation", which is a fully modern inner need.

Measuring The Land by Liu Shiming (I949), Pottery, 24.3×7.3×14.5cm

A Boat on the Yangtze River by Liu Shiming (1956), Glazed Earthenware, 22.2×8.8×8.2cm

Just like the group of distinctive small sculptures created by Matisse, such as Sitting Nude and Reclining Nude, which aims to express the muscle tensions of the human body through body twisting, Read believes that Matisse enhanced the tactile sense of sculpture through small sculpture works with an expressionist tendency, thus tapping into the sensory value that sculpture art may carry. [9]

Reclining Nude by Henri Matisse (1907)

Sitting Nude by Henri Matisse (1925)

Liu Shiming also uses small pottery sculptures and adopts a method of swift and improvisational creation to guide the viewer's attention to the surface of the works, creating a unique "tactile perception" by adding a pottery-based granular texture of pottery and traditional Chinese folk hand sculpture. This is particularly reflected in his works that can best convey his daily life observations. Through the creation of small pottery works including Woman Vendor, Repairing Shoes, Kaifeng Handcart, A Farmer on His Way to Market , and Bathtime, Liu Shiming became more deeply aware of the intrinsic connection between technique, material, and theme expression –“These lively men and women are deeply imprinted in my memory, and they are also the source of my work creation. I do not limit my pottery works to any specific form, and I use any clay that is available to me. I cannot hold back the urge to quickly produce the images from my memory and instantly squeeze them out in the fastest way possible. I do not want meticulous and complete forms, but only to vividly create the characters in my mind." [10] With specific materials and methods, Liu Shiming has utilized the special textures on the surface of pottery clay strips to quickly capture the relaxation and vividness that occur in the dynamic moments of the human body, thereby causing the audience to experience and imagine between the material, the body, and life experience.

Kaifeng Handcart by Liu Shiming (1980), Glazed Earthenware, 26.5×11.4×13.3cm

A Farmer on His Way to Market 1 by Liu Shiming (1980), Pottery, 18.5×8.2×13.1cm

Lovers by Liu Shiming (1983), Pottery, 17×10.3×8.8cm

Repairing Shoes by Liu Shiming (1984), Pottery, 20.3×9.5×12.9cm

03. Eclecticism and "China Practice"

Liu Shiming’s important contribution as recognized by most researchers is what is called "China Practice", which he has comprehensively been instilled with from traditional Chinese folk art forms, including sculpture, Chinese opera, and music. Just like Rodin, Bouchard, Bourdelle and other modern sculpture pioneers who returned to the Renaissance and even medieval art, or modern artists such as Picasso, Gauguin, and Henry Moore who exhibited an eclecticist attitude of free borrowing and integration of various art forms and styles, Liu Shiming has returned and attempted to develop specific techniques and extracted artistic elements from traditional Chinese sculpture. His experience of restoring cultural relics at the Museum of Chinese History from 1975 to 1979 gave him conscious and selective access to the simplistic and exaggerative aesthetics of Han dynasty figurines. By studying the characteristics of ancient Chinese sculpture, he deepened his understanding of the aesthetic views and craftsmanship styles of ancient Chinese people. He marveled at the transformation, imagination, and grandeur of Shang Dynasty bronze artifacts, the imposing presence of stone figures and beasts in Song Tombs, and the expression of strength and speed in Han Dynasty sculptures. Ancient Chinese art used an extremely subtle, solemn, and serene way to express the inner world of the depicted objects in a certain internal language. The various types of vivid portrayal of the ancient working people intoxicated Liu Shiming. He once exclaimed, "In the imitation process, I deeply felt that my sculpture method was not good. The ancient people had a profound understanding and acquired flexible and free techniques. I profoundly know that my techniques are not precise, not mature, not bold, not comprehensive, and inadequate to express what I want to convey."[11]

Someone Who Wants to Fly 1 by Liu Shiming (1982), Pottery, 17.5×9.1×24.3cm

Boatmen on the Yellow River 1 by Liu Shiming (1983), Pottery, 34.7×13.7×9.9cm

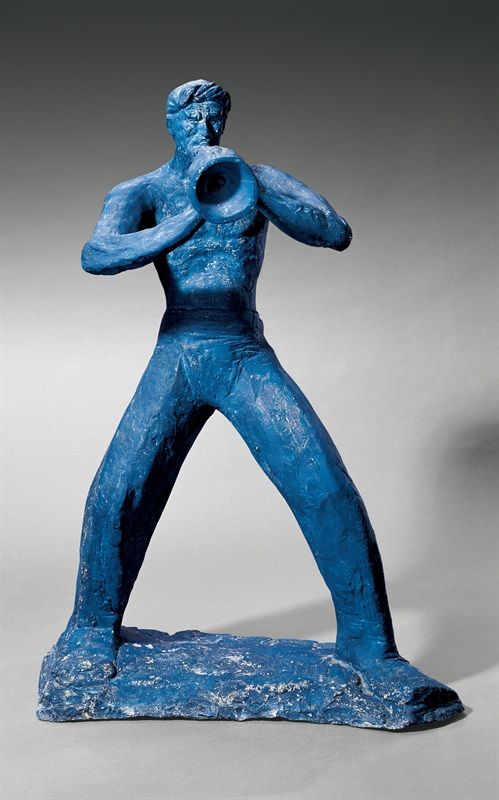

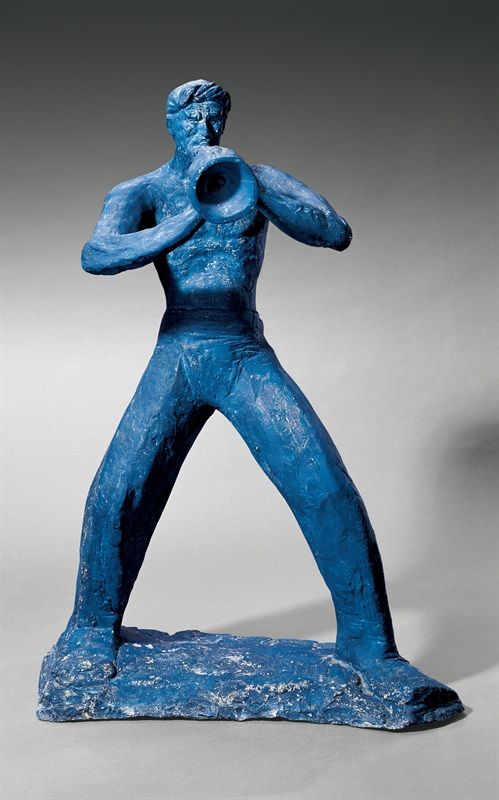

Man Playing Suona 1 by Liu Shiming (1982), Bronze, 17.6×15.8×34.9cm

Farmer and Cart by Liu Shiming (1983), Pottery, 26×6.9×7.7cm

Fusion 1 by Liu Shiming (1986), Plaster, 31.2×14.6×29.1cm

Based on reflections on his previous artistic techniques and ideas, Liu Shiming began to become freer from confinement to the techniques per se. Many of his works, such as Man Playing Suona1, Man Playing Suona 2, Someone Who Wants to Fly, Roaring River Rushing Toward the East , and Ansai Waist Drummer, all bear traces of traditional Chinese art. This allowed Liu Shiming, who has invisibly inherited the humanistic spirit and sensitivity to tactile perception in Rodin's sculpture art, as well as the realistic techniques of the French academic school, to further combine various complex artistic influences with China's social reality, cultural roots, and daily experience, and follow his artistic impulses to create his own sculpture works. It also turned Liu Shiming's sculpture practice into a unique model of the blending of Western techniques and Eastern artistic connotations in the early stages of modern Chinese sculpture, while widening the distance from the Soviet-style sculpture that profoundly influenced the Chinese art establishment at the time. It enabled Liu Shiming to spontaneously blaze a unique path of sculpture thinking, thus opening up the space for further collision and interpretation of Liu Shiming's works in different periods and cultural scenarios.

Man Playing Suona 2 by Liu Shiming (1986), Fiber Reinforced Plastics, 50×50×85cm

Old Man Riding with a Monkey by Liu Shiming (1989), Pottery, 10.6×17.1×15.5cm

Ansai Waist Drummer by Liu Shiming (1989), Bronze, 20.2×11.5×19.5cm

Woman Vendor by Liu Shiming (1991), Painted Pottery, 10.3×14.1×13.7cm

Woman Vendor by Liu Shiming (1991), Painted Pottery, 10.3×14.1×13.7cm

Sheepskin Raft 5 by Liu Shiming (2000), Bronze, 17×12.2×19.5cm

Sheepskin Raft 5 by Liu Shiming (2000), Bronze, 17×12.2×19.5cm

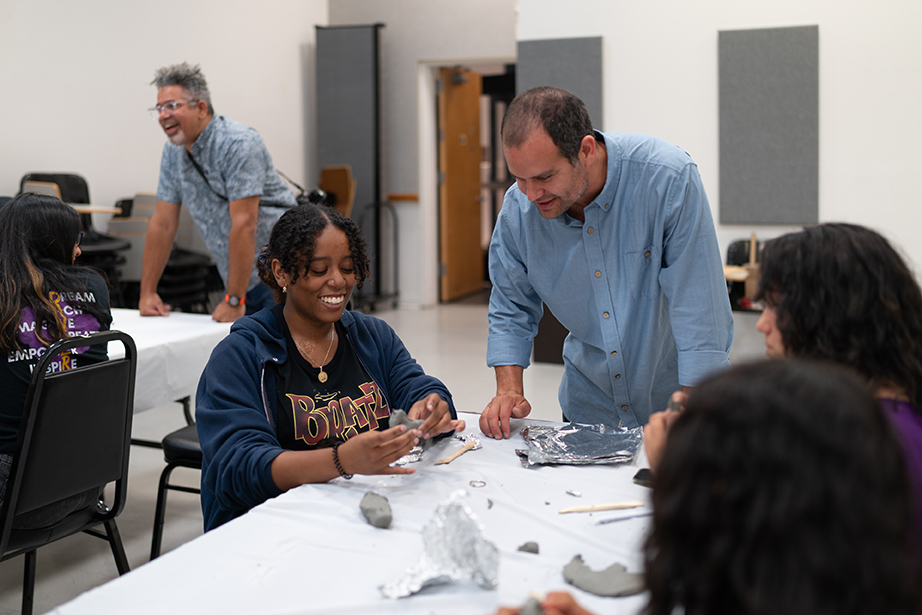

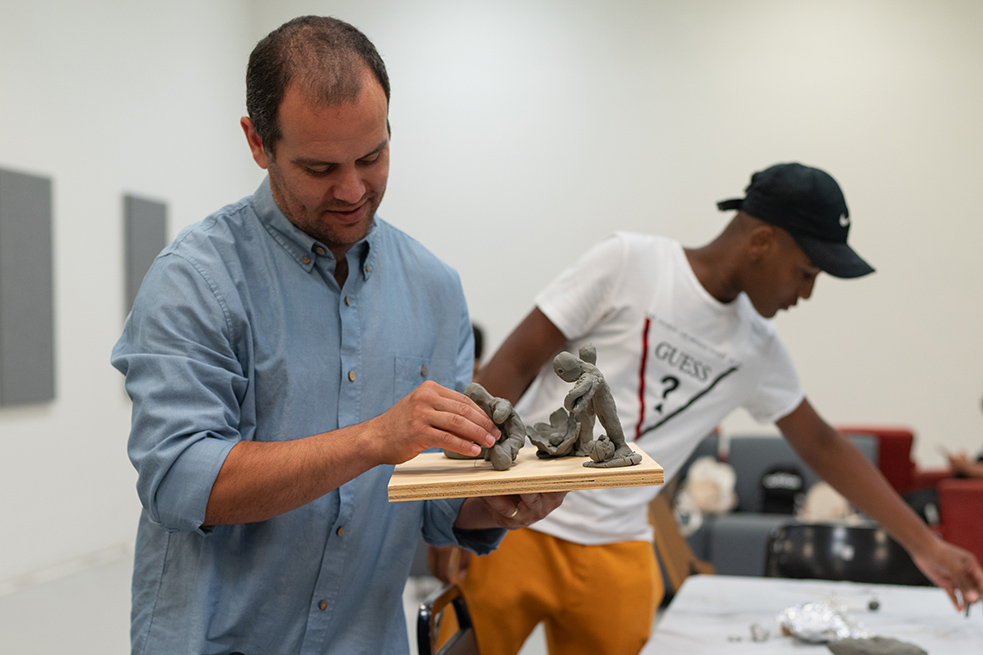

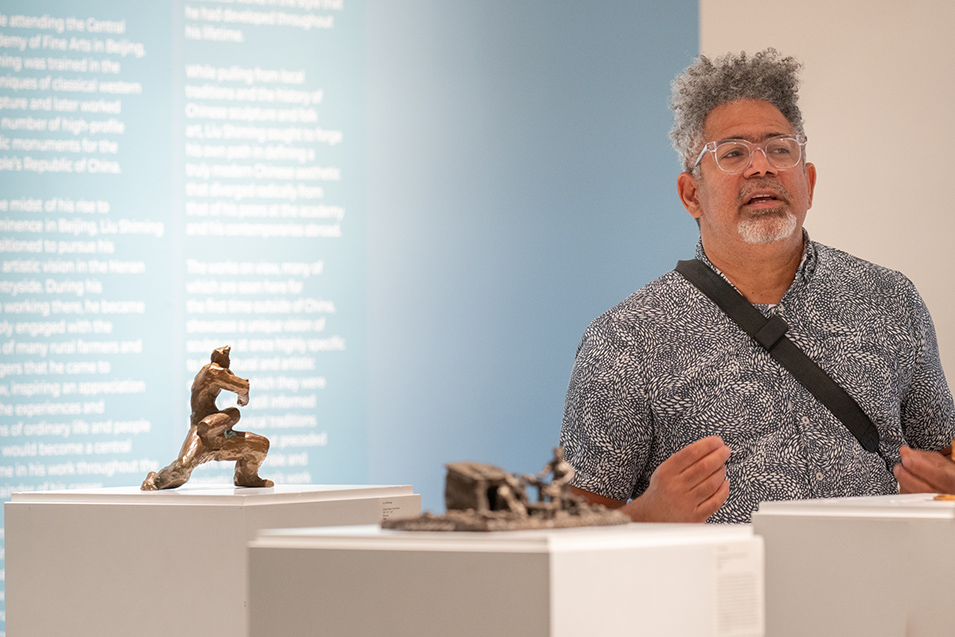

Just as acknowledged by Ashar Mobeen, the curator of the exhibition “IN THE HEART OF THE BRONZE: A Liu Shiming Experience”, the initial intention of the show was to reveal the voices of those who have been marginalized in history from the perspective of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOCs) in the visual art world. The feedback received by Liu Shiming from several overseas exhibitions has always been echoed with perspectives widely regarded as "contemporary themes", such as periphery and center, identity issues, and daily life. This has enabled Liu Shiming, who has consistently been seen in China as someone who excels in learning techniques from traditional Chinese sculpture, seeks themes, emotions, and even identity attachment from the world of Chinese folk customs, buries himself in drawing inspiration from the social life around him, and thus creates an indigenous Chinese method of sculpture to get some kind of "parallel" feedback voices and discussions from overseas. Those small sculptures of Liu Shiming that “cleverly capture these beautiful and intimate scenes in daily life” [12], even though they were created and occurred a decade or even decades ago, can still provide an open entrance for us to repeatedly examine the contours and connotations of modern Chinese sculpture in today's experience-based discourse, even when they are now placed in completely different cultural situations.

By Meng Xi

[1] Liu Libin, Sculpture Teaching at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris in the 1920s and 1930s

[2]Re-Searching for the "Sculpture Gene": Three Traditions in the Teaching System of the Sculpture Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, https://www.cafa.com.cn/cn/news/details/8329954

[3] Qian Shaowu, A Review of the 38-Year History of the Sculpture Department

[4] Shao Dazhen, Ten Lectures on Western Modern Sculpture

[5] Gu Chengfeng, When Did Modern Chinese Sculpture Begin?

[6], [9] Hebert Read, A Concise History of Modern Sculpture

[7], [10], [11] Liu Shiming, The Sculpture Life.

[8] Richard Vine Talking About Liu Shiming.

[12] IN THE HEART OF THE BRONZE: A Liu Shiming Experience Grandly Opened at the Western University in Canada. http://liushimingsculpturemuseum.com/cn/exhibition/details/2693