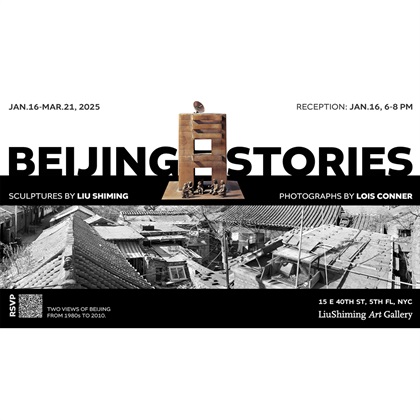

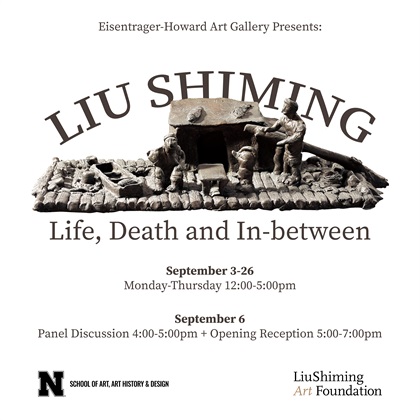

At 6:00 pm local time on October 28, 2019, “Departure and Return: Liu Shiming’s Sculpture” commenced at the Asian Cultural Center of New York. This exhibition was the first stop of Liu Shiming International Sculpture Tour organized by the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), in which nearly 40 bronze sculptures cast by Liu during his lifetime were displayed. The exhibition had three academic sections: “A Wanderer with a Halo: From Metropolises to the Remote Countryside”, “In Search of the Way Home: The Spectrum of Liu Shiming’s Sculptural Language”, and “Home: Liu Shiming’s Real World and Ideal World”. This allowed viewers to appreciate and understand Liu’s contemporary twist as his work is rooted in Chinese folk sculpture traditions. Showing viewers the distinctive and fresh contributions that Chinese modern and contemporary sculptors have made to world sculpture will also improve understanding and exchange between the cultural communities in China and the United States.

Exhibition View

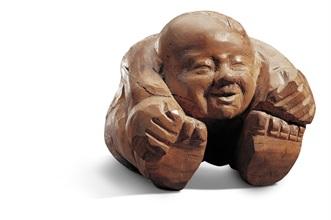

On December 24, 2018, the Liu Shiming Sculpture Museum was established at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and it is dedicated to the research and exploration in the artworks by Liu Shiming as well as their historical significance. Liu Shiming (1926-2010) was a famous Chinese sculptor and a representative of the first generation of sculptors cultivated by the Central Academy of Fine Arts since the founding of People’s Republic of China. Born in Tianjin to a family of intellectuals, he was enrolled in the National Art School in Beiping (now the Central Academy of Fine Arts) in 1946, where he was supervised by Wang Linyi and other famous sculptors who had studied in France. He was then appointed as a college teacher in 1950 for his outstanding performance. During his ten years of teaching, he created and participated in the creation of a number of sculptures that reflected the major historical changes of the country, such as “Measuring the Land” and “Splitting the Mountains to Let the Water Flow”. However, as his name and works were gaining recognition, he chose to leave Beijing and apply to go to Henan Province in the Central Plains of China, turning his attention to ordinary people, from whom he drew inspiration and nourishment. He relentlessly pursued his art for the next decade, which was named “Chinese methods” in order to distinguish it from the popular mainstream sculptural styles of the time. Using what he called “Chinese methods,” he recorded and presented myriad facets of daily life among the average people of his times, and with nearly half a century of practice and research under his belt, he found a distinctively Chinese path that is markedly different from the concepts and forms of Western sculpture. His work enriched and broadened the development of modern Chinese sculpture, which was rooted in the ordinary lives that have existed in China for thousands of years, reflected the popular will on the lowest rungs of society, and presented the popular sentiments of the Chinese people. Liu’s work contains a respect for every individual, as well as his pursuit and expression of freedom. He provided more ways for us to understand the world, ourselves, and human nature, thereby enriching both the depth and breadth of our knowledge.

Opening Ceremony of the Exhibition

From left to right: Liu Wei, Liu Shiming’s son; Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts, CAFA; Hongmei, Associate Professor of CAFA, Curator of the Exhibition

Group Photo of Guests

Professor Wang Shaojun, also a sculptor and Deputy Party Secretary of CAFA, mentioned in his Preface to the exhibition, “This exhibition of Liu Shiming’s sculpture is closely related to an academic project, and as its director, I have a deep appreciation of the meaning that Liu and his art have for this project. We study how ancient Chinese art maintained its natural qualities when it met with Western art, and we have continued to study ‘Chinese methods’ that embody a Chinese context.

We have taken the case study of Liu as a starting point. We will focus on artists and artistic phenomena within Chinese modern sculpture that have involved modern transformations of Chinese modes of sculpture and we will examine modern art practices that diverge from Western narratives of modern styles; they have Chinese characteristics, and they are rooted in the modern transformation of Chinese traditional contexts and local experiences that have emerged over hundreds of years of Chinese sculpture. I think that Liu’s art archive is like a key that allows us to open the door to China’s original art, thereby building a system of creation and study for Chinese contemporary art that truly showcases human civilization and reflects Chinese cultural qualities.”

Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts, CAFA, delivering a speech on the opening ceremony

In his speech, Professor Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts, CAFA, said: “Liu has spent over ten years making ceramic sculptures, which bear many similarities with those from the Han dynasty tombs. Some of the subjects are very much alike, reflecting the changes and the unchanged in people’s lives since the Qin and Han dynasties. The images in his work cover a wide range of themes, but his artifacts, animals, and buildings are all presented around the life of humans. The protagonists of human life are the men and women, the projections of their spirits. Liu’s heart flies using his hands and clay. What he calls memory is a span of time and space, a seeming past that meets him in the present moment and turns out to be a living reality. Today, if we can understand Liu, it is because we know we are imperfect, disabled, and suffering from all kinds of polio. We are tempted by interests, prestige, and greed, and we now have degraded health, atrophied perception, numb nerves, and conceptualized feelings. We increasingly rely on various tools to extend the ability we should have had to meet the needs to degrade ourselves. We increasingly rely on strong stimuli to satisfy our numb nerves, strengthen the conceptualized feelings and even go to extremes on the basis of an already strong conceptualized tendency, as if what we do can prove we are still alive and living a meaningful life. We may be able to get brave after knowing our shortages and train our ‘eyes’ that should have been bright in the world of darkness, to tap into our own abilities, to perceive the subtleties and infinity of nature, and thus, discover ourselves and testify our value.”

Hongmei, curator of the exhibition and Associate Professor of CAFA, delivering a speech on the opening ceremony

In her speech, Associate Professor Hongmei, also the curator of Liu Shiming International Sculpture Tour, said, “This exhibition is the presentation of my ongoing research on Liu Shiming, which includes his modernization of the traditional Chinese clay and ceramic sculptural language pioneered by Liu, his pure and simple fraternity of the common people, his promotion of the localized sculptural language with China’s own unique aesthetic norms, and his modernization of the ‘modeling’ tradition developed from China’s own cultural lineage, which is different from the Western sculpture tradition. This is where his tragedy and contribution lie, and this is what attracted me to devote a great deal of effort to the research. In recent years, I have devoted myself to the study of the development of Chinese art that presents a narrative and a reflection of the meaning of modernity that is different from that of the West, with its own Chinese characteristics.”

Qian Jin, Deputy Consul General of the Consulate General of China in New York, said in his speech, “Most of Liu’s works reflect the characters and scenes that he saw and experienced. It can be said that his works are a vivid record of Chinese life in his era. By comparing it with styles that are current in China, I believe American friends can see the great changes that have taken place in China in the past decades.”

Exhibition View

Victor Delfin, a well-known Peruvian sculptor in his 90s, sent a letter of congratulations, writing, “Allow me to extend my heartfelt congratulations on the exhibition of Liu Shiming’s sculptures! New York is one of my most beloved cities. This world-touring exhibition will bring enjoyment for visitors from the United States and Australia. Mr. Liu’s sculptures are true artistic treasures. They are rooted in Chinese tradition, yet bursting with innovation and energy.”

Dionisio Cimarelli, a renowned Italian sculptor who currently teaches at the New York Academy of Art and has lived in Shanghai for many years, told a journalist from Xinhua after viewing the exhibition, “Liu’s works are great and have a strong Chinese cultural dimension.” He said that such an exhibition showcasing Chinese culture and art is meaningful in itself and is very conducive to the American public’s awareness and understanding of this unique and noteworthy artist.”

A group photo of the four scholars who joined the Departure & Return: Liu Shiming’s Sculpture Symposium at Columbia University (from left): Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts at the CAFA, Dionisio Cimarelli, sculptor and painter at the New York Academy of Art, Aima Saint Hunon, French sculptor and painter, and Hongmei, curator and Associate Professor of CAFA.

(From left) Hongmei, curator and Associate Professor of CAFA; Andy Serwer, Editor-in-Chief of Yahoo Finance; Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts of CAFA; and Liu Wei, son of Liu Shiming

(From left) Associate Professor Hongmei, Professor Ma Lu, Professor Cao Chunsheng, a well-known Chinese sculptor of CAFA, Liu Qiuqiu, and Liu Wei, Son of Liu Shiming.

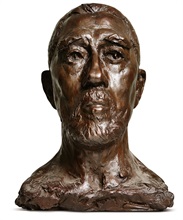

(From left) Liu Wei, son of Liu Shiming, Professor Cao Chunsheng, a famous Chinese sculptor and member of CAFA, Professor Ma Lu, and Associate Professor Hongmei, pose in front of the bronze statue of Liu Shiming sculpted by Professor Wang Shaojun, Deputy Party Secretary of CAFA and Academic Advisor of the exhibition.

(From left) Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts of CAFA, Qian Jin, Deputy Consul General of the Consulate General of China in New York, and Associate Professor Hongmei, curator of the exhibition

Professor Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts of CAFA (first from left), and Andy Serwer, Editor-in-Chief of Yahoo Finance (first from right)

Professor Ma Lu, Dean of the School of Fine Arts of CAFA, and Harvey Citron, Chair of Sculpture Department at the New York Academy of Art

The opening event was also attended by Jenny Roosevelt, collector and curator of Latin American art; Dionisio Cimarelli, sculptor and painter; Aima Saint Hunon, sculptor and painter; Ana de Orbegozo, sculptor and painter; Harvey Citron, sculptor and Dean of the Sculpture Department at the New York Academy of Art; Mia Diehl, Director of Photography at Fortune Magazine, Andy Serwer, Editor-in-chief of Yahoo Finance, Robert C. Morgan, New York Editor for Asian Art News and World Sculpture News; Malissa Lazarov, Executive Director of the Advisory Board of Gagosian Gallery; Douglas Alden, Professor at Hunter College and TV Executive Producer; Bette Hyman, art collector; Penny Gorman, art collector; Frank Ryan, architect; and Zhou Xiaozheng, President of Xinhua News Agency North America.

Exhibition View

In order to deepen the study of Liu’s sculpture, a symposium on his art was also held at Columbia University on November 6. Jim Cheng, Director of the C.V. Starr East Asian Library at Columbia University, Dionisio Cimarelli of the New York Academy of Art, visual artist Aima St Hunon, Professor Ma Lu, Director of the School of Fine Arts at CAFA, and Associate Professor and curator Hongmei engaged in a dialogue to discuss and exchange views on the value of Liu’s sculpture in the history of modern Chinese sculpture.Standing in the twenty-first century, when we look back on Liu Shiming’s half-century of sculptural explorations, we must marvel at his foresight and self-awareness. He was a rare intellectual of his time who always maintained clear understandings and preferences with regard to Eastern and Western culture. He was an intellectual who always retained pride and respect for his own culture. He was always faithful to his own cultural conscience and aesthetic tastes, and he set his own course, keeping his distance from trends and intellectual talking points. He persisted in his lonely, solitary exploration of Chinese sculpture using his own “Chinese methods.”

The exhibition remained on view until November 8, 2019. The second stop of the international tour was in Washington, D.C. on November 14, 2019.

By Wang Chunyuan

Photograph by Qi Siyang

(Some images courtesy of Asian Cultural Center)

I.Leaving with a Halo on His Head: Departing the Capital for the Countryside

The Prosperous Capital

1926

Liu was born in Tianjin to a family of intellectuals. His father, Liu Baoshan, studied mechanics at the University of Detroit Mercy from 1926 to 1931. His mother, Guo Suyu, graduated from the Tianjin Women’s High School. Liu Shiming was educated in traditional culture from an early age. As a child, he studied Han seal carving and Northern School landscapes.

1946

Liu enrolled in the Beiping Fine Arts School (now the Central Academy of Fine Arts), where he studied with Wang Linyi and Hua Tianyou, members of the first generation of Chinese sculptors to study in France. Liu studied classical sculpture from the French academic school, as well as Rodin’s modern ideas about sculpture.

1950

Liu’s graduation work Measuring Land won first prize in the “Red May” exhibition, and it was published in the first issue of The People’s Pictorial in 1950. At the recommendation of CAFA President Xu Beihong, Measuring Land was sent to Prague to participate in “Prague: World Student Gathering Art Exhibition.” It was collected by the National Museum of Czechoslovakia (now the Czech National Museum). He graduated in July, and he stayed at the university to teach at the recommendation of President Xu Beihong.

1951

Liu enrolled in the graduate program for sculpture at CAFA. That same year, he was transferred to the Monument to the People’s Heroes sculpture studio. He participated in creating, researching, and discussing the Monument to the People’s Heroes, and he assisted Wang Bingzhao in sculpting Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Jintian Uprising.

1955

Liu was transferred to the China Sculpture Factory (later the Central Academy of Fine Arts Sculpture Research Institute).

1958

A 7.1-meter-high version of Cutting Through Mountains to Bring in Water was placed by the Safeguarding Peace Archway at Beijing’s Zhongshan Park for the anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. The work was soon published in The People’s Daily, and American author Anna Louise Strong used it as the cover image for The Rise of the Chinese People’s Communes, a book about the Great Leap Forward.

1959

Baoding, a city in Hebei Province, purchased Cutting Through Mountains to Bring in Water and placed it in Dongfeng Park, where it stands to this day. Cutting Through Mountains to Bring in Water was widely circulated as the spirit and image of 1950s China, making Liu a household name.

The Remote Countryside

1956

Liu traveled to Wuhan to work on the Underwater Work sculpture group, a piece of the Hanyang Bridgehead on the Yangtze River Bridge. While he was standing at a small station on his way through Sanmenxia one night, he heard the slow melodies of Henan opera floating out of a small house in the pitch-black distance. After that, he became fascinated by Henan opera, and he began to yearn to live in Henan.

1961

In June, he decided to leave the Central Academy of Fine Arts and the China Sculpture Factory and move to Henan Province. He chose to transfer to the Zhengzhou Art Academy in Henan. In September, he was transferred to a position in the Art Department at the Kaifeng Normal Academy (formerly Henan University).

1966

During the Intellectual Re-Education Campaign, he was sent to the Daichai Sub-Forest at the Juqi Forestry Center in Minquan County for thought reform.

1969

The man who left with a halo on his head for the distant countryside began to think about Beijing, the city he had left nearly ten years before.

II.Finding the Road Home: Liu Shiming’s Evolving Sculpture

Here, we see works created as Liu Shiming studied the classic sculpture of the French academy, as well as works influenced by Rodin’s ideas about modern sculpture. There are also works showing the elation of the people in the early years of the establishment of the People’s Republic, burning with romanticism. This section also highlights classic works that won the young sculptor great acclaim.

Here, we see a young sculptor who had not been affected by praise; from the breadth of people’s everyday lives and from the historical artifacts at the National Museum of China, he discovered a new breakthrough in his art, as well as an artistic path that was truly his own.

Here, we see the evolution of Liu Shiming’s sculptural language over the course of sixty years, and we can see an artist’s departure and return—how he finally found the road home.

1970

After several setbacks and much homesickness, Liu was transferred to Baoding in Hebei, which was not far from Beijing, to work on a large-scale clay replica of Rent Collection Courtyard in Lotus Pool Park. As a sign of respect, he was given a small single-room studio he called “a small square kettle.” During his four years in Baoding, he spent his leisure time sitting in deep thought at the lotus pond by his “small square kettle,” remembering how he arrived there. This period in time was important for Liu Shiming’s interior transformation. To commemorate this time, he created a copper seal with the words “A Small Square Kettle.”

1971

After several setbacks, he was formally transferred to the Baoding Mass Culture and Art Center in Hebei.

1974

Liu was homesick, so he arranged for an early retirement, which allowed him to return to his hometown of Beijing after 15 years. Once back in Beijing, he restored and replicated artifacts at the National Museum of China.

After seven years of work, he established and persisted in his artistic path, focused on the localization of sculpture. If Chinese traits had appeared in Liu Shiming’s previous sculpture spontaneously, spending seven years working with Chinese artifacts from various dynasties compelled him to consciously focus on Chinese historical ceramics. He was determined to use “Chinese methods,” which are different from the concepts and methods of Western sculpture, to find his own path in sculpture.

1980

After working for seven years, he returned to teach in the Sculpture Department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. In CAFA’s Electric Kiln Studio, he fired his own clay works, creating more than one thousand pieces in fifteen years.

1995

Liu Shiming finished his tenure at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and continued to work at his home in Beijing.

1998

“An Exhibition of Liu Shiming’s Sculpture” was held at the Central Academy of Fine Arts Corridor Gallery, and the catalog Liu Shiming’s Works was published.

1999

Liu was interviewed for the CCTV-1 program “Sons of the East.”

2005

“Local: Liu Shiming’s Sculptures” and a symposium were held at the Central Academy of Fine Arts Sculpture Research Institute. Liu was interviewed for the CCTV-10 program “Figures.”

2006

“Free Daisies: An Exhibition of Liu Shiming’s Sculpture” and a symposium were held at the National Art Museum of China. Liu was interviewed for the CCTV program “Sons of the East” a second time.

2010

In May, Liu Shiming died at the age of eighty-four.

III.Home: Liu Shiming’s Real and Ideal Worlds

In the course of Liu Shiming’s eighty-four years, he always conscientiously yet distantly lived, felt, experienced, and expressed real and ideal worlds. Like sunshine and storms in nature, he wanted to quietly accept the impermanence of life and the diversity of human nature, while always maintaining utter innocence. He spent sixty years exploring the art of sculpture, recording his life and the journeys of intellectuals of his generation, which bear some similarities to the legendary journey of ancient Greek hero Odysseus.

In a sense, Liu Shiming lived by his art, but he lived at a time that did not require him to singularly pursue his artistic ideals. As a result, he departed and returned, as he navigated the long search for home. This is his spiritual home, with Eastern and Western, ancient and modern explorations of sculpture, but it also represents his hopes and hard work as he drifted for fifty years, pursuing peace and spiritual respite.

Curator’s foreword

A member of the first class of sculpture students admitted to the Beiping Fine Arts School (precursor to the Central Academy of Fine Arts), Liu Shiming (1926-2010) began studying sculpture in his youth, trained by Wang Linyi and Hua Tianyou, part of the first generation of Chinese sculptors to study in France. After five years, Liu Shiming had internalized classical sculpture from the French academic school, as well as Rodin’s modern ideas about sculpture. As a result, his 1950 graduation piece attracted particular attention. Measuring Land won first prize in the “Red May” exhibition at CAFA and was recognized by president Xu Beihong. The work was selected by the Central Academy of Fine Arts for an overseas exhibition and was later collected by the National Museum of Czechoslovakia (now the Czech National Museum). Liu also petitioned Xu Beihong to allow him to remain at the academy to teach. The next year, Liu Shiming enrolled in the graduate program for sculpture at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and graduated.

After more than ten years of exploration and creation, at a time when he had experienced honors and successes, Liu Shiming chose to listen to his heart. In 1961, he left the busy capital city, following the melodies of Henan opera to poor villages in China’s Central Plains. He spent ten years in various places in Henan, followed by four years in Baoding in Hebei. He engaged deeply with these poor villages, he shared in the difficulties of these rural people, and he came to deeply appreciate the state and meaning of life.

Liu eventually became homesick and he allowed the tides of fate to carry him back to Beijing. In 1974, he began working at the National Museum of China, where he spent seven wonderful years cleaning, restoring, and replicating treasured artifacts from China’s past. He was immersed in the distinctive and lovely modeling aesthetics of various ancient pieces of China’s long history.

In 1981, Liu Shiming’s alma mater, the Central Academy of Fine Arts, opened its arms to an artist who had wandered elsewhere for twenty years, and he returned to teach in the Sculpture Department. He fired his own clay pieces, making nearly 2,000 works over twenty years.

In a sculpture career spanning more than 60 years, Liu Shiming always maintained a clear distance from the ideas and forms of Western sculpture, which held a commanding position at the time. Instead, he persistently grounded himself in a Chinese local context, uncovering various kinds of folk art within the Chinese tradition, and perpetuating ancient Chinese modeling methods. He advocated for drawing nourishment from past clay sculpture, making it contemporary using what he called “Chinese methods.” This was a path toward a local mode of Chinese sculpture that diverged from the ideas and forms of Western sculpture.

Liu Shiming’s long and arduous journey, exploring “Chinese methods” of sculpture, was not unlike that of the legendary journey of ancient Greek hero Odysseus. Liu Shiming lived by his art, but he lived at a time that did not require him to singularly pursue his artistic ideals. As a result, he departed and returned as he navigated the long search for home. This “home” is his spiritual home of Eastern and Western, ancient and modern explorations of sculpture, but it also represents his hopes and hard work as he drifted for decades, pursuing peace and spiritual respite. The exhibition will present nearly forty bronze works that Liu Shiming personally cast during his lifetime in three sections entitled “Leaving with a Halo on His Head: Departing the Prosperous Capital for the Remote Countryside,” “Finding the Road Home: Liu Shiming’s Evolving Sculpture,” and “Home: Liu Shiming’s Real and Ideal Worlds.”

“Departure and Return: Liu Shiming’s Sculpture” is the first show in the “Chinese Methods: A Liu Shiming Traveling Sculpture Exhibition” series organized by the Liu Shiming Sculpture Museum at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. The traveling exhibition will launch in New York, an international art capital, so that American and global audiences and art professionals will come to understand Liu Shiming’s unique sculptures and engage with the “Chinese methods” of sculpture that he proposed and pioneered. In this way, the world will recognize the hard work and contributions that modern and contemporary sculptors from China and the Central Academy of Fine Arts have made to sculpture. Viewers will also come to appreciate the modernization that has taken place in the last one hundred years of Chinese sculpture, which has uniquely Chinese characteristics and is rooted in Chinese traditional and local experiences—this mode is entirely different from the modern Western narrative. This perspective will enrich the diversity of narratives of modern art history in the world.

Hongmei

Associate Professor, Graduate Advisor, Ph.D., Central Academy of Fine Arts

Head of the Theory Publishing Department, CAFA Art Museum

Managing Curator, Liu Shiming Sculpture Museum at the Central Academy of Fine Arts

Preface (Academic Advisor’s Words)

This exhibition of Liu Shiming’s sculpture is closely related to an academic project, and as its director, I have a deep appreciation of the meaning that Liu Shiming and his art have for this project. We are studying how ancient Chinese art maintained its natural qualities when it met with Western art, and we have continued to study “Chinese methods” that embody the Chinese context.

We have taken the case study of Liu Shiming as a starting point. We will focus on artists and artistic phenomena within Chinese modern sculpture that have involved modern transformations of Chinese modes of sculpture and we will examine modern art practices that diverge from Western narratives of modernity; they have Chinese characteristics, and they are rooted in the modern transformation of Chinese traditional contexts and local experiences that have emerged in hundreds of years of Chinese sculpture. I think that Liu Shiming’s art archive is like a key that allows us to open the door to China’s original art, thereby building a system of creation and study for Chinese contemporary art that truly showcases human civilization and reflects Chinese cultural qualities.

We could say that, after the massive social change that was Reform and Opening, modern China once again confirmed its values. This understanding will invariably bring about a wider practice of those values. Today, we are bringing this exhibition to friendly nations for precisely this reason.

Here, I would like to introduce Associate Professor Hongmei, the managing director of this project. As curator of the exhibition, she clearly employed her capabilities and wisdom, and through her deeper analysis of Liu Shiming’s life and art, she will certainly give the viewer a valuable chance to comprehend and contemplate this artist, and I eagerly await the results.

Wang Shaojun

Professor and Ph. D Advisor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts

Deputy Party Secretary at the Central Academy of Fine Arts

Director of the Liu Shiming Sculpture Museum at the Central Academy of Fine Arts

September 25, 2019

Postscript

Long Live Savant II

“Savant II” was his nickname. It was a nickname his brothers gave him growing up. Even now, that’s what his brothers call him. My aunt says that, when they were young, she was tidying up his room in their home, and she discovered a wooden board with the words “Savant II Studio” hanging there.

He was an introvert and he liked to read. He really liked reading about the adventures of the martial arts heroes, and he also liked talking about them. He had a great memory, and he could remember those stories very clearly. More importantly, he thought those stories were real. He had a great imagination, and liked being in quiet places. It was as if he was seeing those heroic stories in his head like a movie, and he fantasized about participating in them, acting on his strong sense of justice.

He would do things differently from normal people. For example, in his youth, he carved a wooden stick into the shape of a small penis. He painted it pink and placed it in the living room. This made his father very uncomfortable; he said, “Put that in your room. If you put it here, people will think that I carved it.”

When he went to university, he shaved his head, wore a black shirt and black pants, and tied up his trouser legs. In the silence of the late night, he would go alone to the school’s boiler room to practice his night vision, or in the middle of every night, he would sit and meditate in his dorm. During the day, he took a coffin-shaped pencil case of his own design to class.

As a child, he contracted polio, which later developed into progressive muscular degeneration. His arms and legs became thinner and his belly became larger. To remove what he thought was oil from his belly, he once tried to drink dishwashing liquid. All his life, he searched for ways to cure himself—he often wrote prescriptions for himself. Worried, his father even called him Doctor Liu. He prescribed things for himself, and he often took the wrong medicine, so he always had handfuls of green beans in his pockets. When he felt unwell, he would eat a few of them. He would ask friends who practiced energy healing for help. He would call them and have them send him energy through the phone to treat him. Sometimes he would take too much medicine, but these methods didn’t work, as they would cause vomiting, diarrhea, and full-body numbness. He couldn’t get out of bed.

In life, he would do things that he thought were brilliant. One time, so that the house could have a more natural breeze, he had workers install air conditioning on the balcony. To prevent someone from stealing his money, he hid the cash in a honeycomb briquette. When the temperature got colder in the winter, in order to save money, he would buy strips of leather to seal the seams in his clothing. When he was an old man, he would be alone in his room, folding newspapers into various kinds of hats, which he would wear. He would wrap himself in a blanket and put on sunglasses as he sat on the sofa and watched TV. When he watched a program, he would shout “Nonsense!” at people telling lies. He would hold his hands in the shape of a gun, and point this finger gun at the TV, making the noise: “Bang, bang, bang!” His pockets were crammed with all kinds of things: heart medication, pens, notebooks, keys, papers, and a Coca-Cola bottle cut into a chamber pot...

Though he received no formal training beforehand, he was accepted to the Central Academy of Fine Arts and became a favorite pupil of masters such as Xu Beihong and Wang Linyi. After he graduated, he stayed at the academy to teach, at a monthly salary of 90 RMB, which was really high for the time. However, he became enamored of the Henan opera performer Ma Jinfeng, and pursued her to Henan and began a life of desperate wandering. In the years that followed, his life became more chaotic. He wandered like Don Quixote, abandoning everything in the process. When he returned to Beijing, his salary was just over 50 RMB. With the help of some friends, he had obtained a temporary position at the National Museum, where he spent eight years replicating cultural artifacts. It was also with the help of those friends that he found a studio at CAFA, where he created more than a thousand little figures.

Most of the time, he was really normal and really calm, to the point that people around him forgot he was there. Because he was so quiet, my family almost lived in a world that ran parallel to his, without much interaction.

In recent years, I have been organizing his papers—he had stuffed drawer after drawer with pictures, documents, letters, identification, and even random cards, prescriptions, some Chinese medicine, a magnifying glass, a lock of hair, and a newspaper clipping... All of this started to unfold before my eyes, surprising me with their complete frankness, sincerity, naturalness, vitality, and color. It was like opening the door to my memories; they corresponded to my more than fifty years of memories of him. I had almost let a treasure trove slip away.

At every stage in his life, he kept a diary in a few different styles. Sometimes, his accounts had no structure, and other times he was letting his emotions loose, but they were lively, truthful, and heartfelt. Those stories seemed to be appearing before my eyes. In order to retain as much of the originality of his stories as possible, we made almost no embellishments. At the end of every diary entry, I told a few stories to give some background about his life and circumstances at that time. In telling these stories, I felt that the parallel lines that he and I lived on could meet. Now, in the fourth spring since his passing, I have finally discovered why he was not of his time, why he didn’t fit in, and why his story was so tragic—the origin story of this old man.

I love him even more. Long live Savant II!

Savant II was always moved by the slightest assistance people were able to give him, and he recorded these little things in his diary and engraved them in his heart. If he knew about what was happening today, I think that the list of people he would want to thank would be very long; not one person would be left out. This gratitude would be sincere, arising spontaneously from his heart. Thank you everyone.

Liu Wei (Liu Shiming’s son)

Drafted on Chinese New Year’s Eve 2014, Supplemented in October 2019